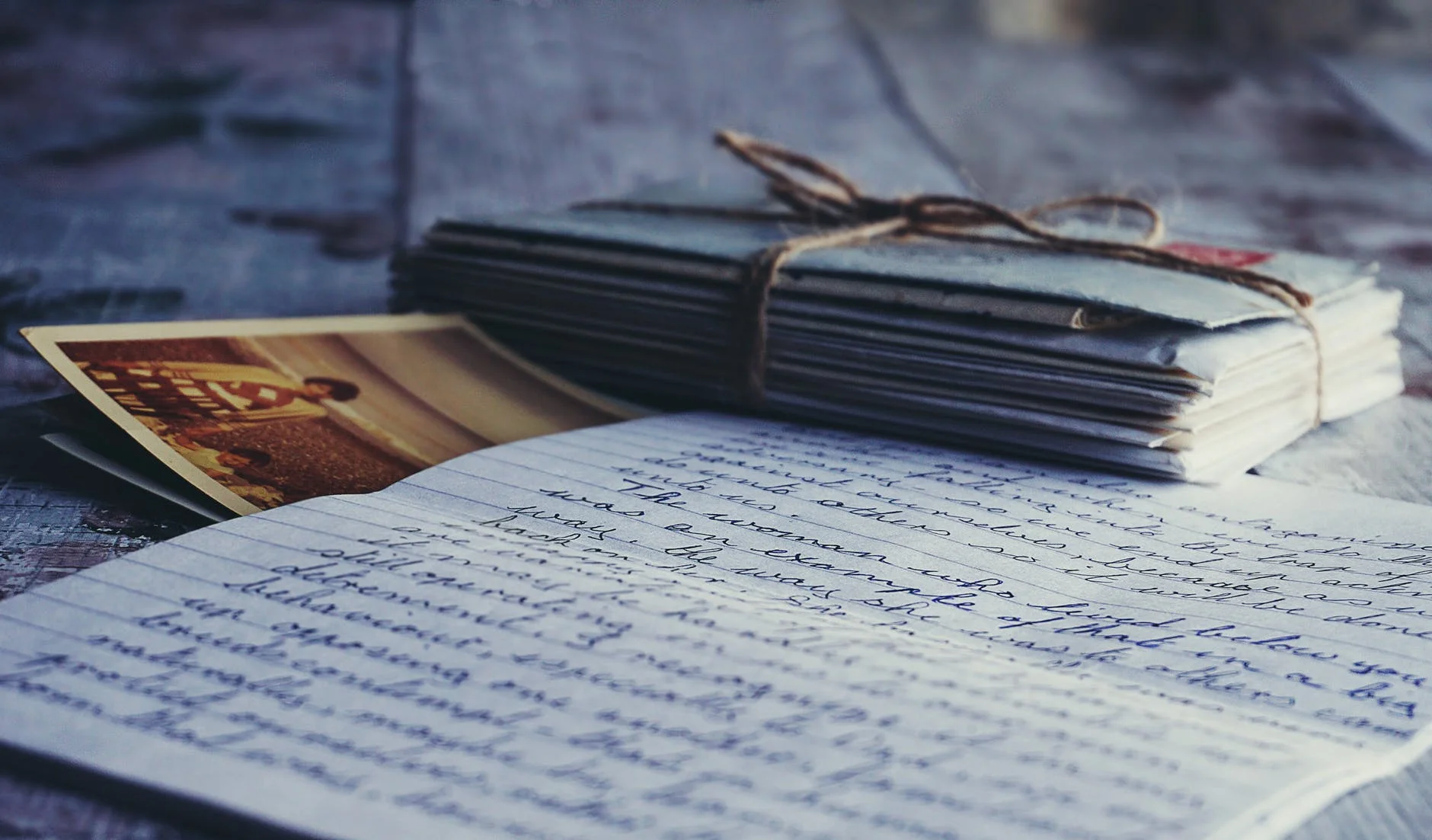

Story 6 - The father figure

A deserted, half fallen apart sports complex, washed constantly by drizzling gray rain. Rust stains your fingertips foxy red if you hang on the bar. I could never hang too long and slowly let my fingers slide off and my body drop on the ground like a sack of potatoes. This uncoordinated kid in wellington rubber boots, very Soviet knitted hat and large mittens, is me.

There, at a dilapidated rusty playground, a few tram stops away from

the nuclear power station both my parents worked at, I stood in my bright yellow wellington boots and could not believe my luck.

I was not a sporty kid but a very cute one. The type who smiled at strangers in the train. In a country where no one smiles in public places per definition, I stuck out, at the age of four already, like a sore thumb. I once got the last Skittles candy from a cleanly shaven punk kid in heavy black boots who was sitting opposite me in a train compartment, on our way to the city center of St.Petersburg. My Mom, taken aback by my boldness, made a motion to try and interfere, but once the kid made an inviting gesture with a hand full of candy towards me, I skillfully jumped off my seat, crawled onto his lap, wiggled myself in a comfortable position and slowly, carefully took the sticky candy from him with the tips of my fingers. I swiftly stuffed them all behind my cheek, as if afraid the punk might suddenly change his mind.

Startled by the open gesture and the trust I had in him, the boy sat motionlessly as if not knowing what to do next with a 4-year-old on his lap, wrapped in multiple layers of clothes like a soft cuddly cabbage. My Mom was always worried I’d get cold and then, naturally, hopelessly ill. “Better a tiny Tashkent experience than a severe North”, she always used to say insinuating that keeping a little too warm is always better than encountering hyperthermia (largely unlikely in the climate we lived in, unless she left me outside overnight). My Mom is a worrier, she’s always been one, she would relentlessly find reasons to be concerned (especially about mine and my sister’s health, and other people’s health if their life would be at a tangent interwoven with ours). This is how I imagine people to turn out who’d been through war or famine, or siege of Leningrad. My Mom (thank G-d) has never been through any of these terrible events, she just grew up in the Soviet Union.

There, at a dilapidated rusty playground, a few tram stops away from the nuclear power station both my parents worked at, I stood in my bright yellow wellington boots and could not believe my luck. We were there to play! My Father was rarely home and when he was, we read or he spoke of his trips but we almost never played outside.

I tried to ignore the sound in my boots every time I took a step. Rain drops found their way inside my boots and now I had my own puddles under my feet with no socks, which we carelessly forgot to put on, too excited at the perspective of playing basketball.

The figure next to me, the Father figure, held the basketball with both hands, and smiled the broadest smile. “Come on, I throw from the chest, you catch at the chest level, keep the knees soft! You got this!”

He walked through life never looking back too much or standing still

to wonder what collateral damage his actions could have potentially had.

My father was shamelessly, unnaturally handsome for the 90’s Russia. At least, this is how I remember him, and so do the black-and-white photos from that time. With a kind wide smile of perfect straight teeth, thick raven hair, tall and broad-shouldered, he used to break hearts carelessly but also seemingly light-heartedly and effortlessly. He was so charming in his recklessness, that almost no one, even my mother, could be mad at him for too long, nor take him too seriously.

He could be very kind but also sharp and curt. He walked through life never looking back too much or standing still to wonder what collateral damage his actions could have potentially had. The trick I learned early on was to ask for something just after he had a cigarette on our tiny balcony in the communal apartment. The nicotine just reached his blood stream releasing the whatever it is nicotine does to our body, and my father was always more pre-disposed to say yes. That day I urgently wanted to play outside with the new basketball he got my older half-brother. I did get what I wanted, having patiently waited for my Father to emerge from the balcony with an acerbic cloud of Yava cigarettes smell around him. It can again be mentioned that, albeit not being a sporty or active kid, I was a sweet and seemingly soft-natured one, so getting what I wanted (provided I wanted it badly enough) was a skill I developed very early. I practiced relentlessly on my Father, as my Mom would fall to my charms later, around my age of 12.

Then, we’d discover I’m above average intelligent (or above average good at remembering random large pieces of information, as this is what the Russian educational system demanded most of a student). My mother believed in the all-conquering power of education, which one day would move me from a 12 square meter room in a communal apartment to a bright future (the time showed she was not utterly wrong). The moment to ask her for things was after I won another award or medal (Russians like to give children medals, for swimming competitions and spelling bees alike). I was not much of a swimming competition kind of girl, but I had this spelling bee business under the knee. Having photographic memory definitely helped but also particular stubbornness, which drives a 12-year old, who wants grape-flavored gum and new jeans and ice cream in the winter. This all required pocket money, which I got if I’d won. This was my Mom’s nicotine kick, her type of cigarette. This was then my moment to ask for things, new clothes, that grape-flavored square block gum, which colored your tongue a deep shade of purple. I wanted it all, so I kept studying and kept winning.

I spent many years to come finding people’s levers and their happy places. But at 4, I only cared for my Mom and Father, for a split of a moment it was just us, us three, and my Father was easy to read.

I cried, cried hard with a nice clunky undertone of despair,

the way only little kids know how to release negative emotions.

We stood at the playground and he kept throwing the ball. I caught heavily, with my entire body, the ball too big for how small my body was. “Come on! You got this!” Throw, catch, meek throw back, and again. At some point the ball was too wet, my arms tired, and my fingers slipped allowing the weight of the ball to land right on my face with a sharp thump. Thin, almost parchment and see-through white skin opened just above my left eye brow. Blood streamed down my face, covering my eyes with a thick curtain, with a smell and taste of iron. I smudged it with my palms to be able to see again and a figure of my Father emerged from behind the flow of blood. He had a lost expression on his face, “How did all this happen?” his eyes were asking.

I cried, cried hard with a nice clunky undertone of despair, the way only little kids know how to release negative emotions. I cried not because it hurt, but because I was scared I let my father down. He had never assured me otherwise. I cried because I thought I’d never make him proud again and never become a basketball player. One of these fears turned out to be very true.

I remember standing in the middle of our large, always cold, shared kitchen, my face still covered in drying up blood, the texture of molasses, stumping my feet inside the boots, my heels going freely up and down with a squelching sound in the extra space where socks were meant to be. My Mom was all sorts of angry, for my Father cooling a kid and getting me a lung infection (no less), and hitting me in the face with a ball, scarring my pretty tiny face for life.

Later, while splashing in a warm bath, my Mom’s kind hands washing off blood off my face with dark ochre chunk of soap, I stopped crying. I had forgotten all about disappointing my Father and my failing sports career. The scar above my eye brow turned out quite cute and barely visible. This day is the first happy memory I have of my Father. I would go on through life collecting very few days like this together, or any days for that matter.